By Trey Williams

By Trey Williams

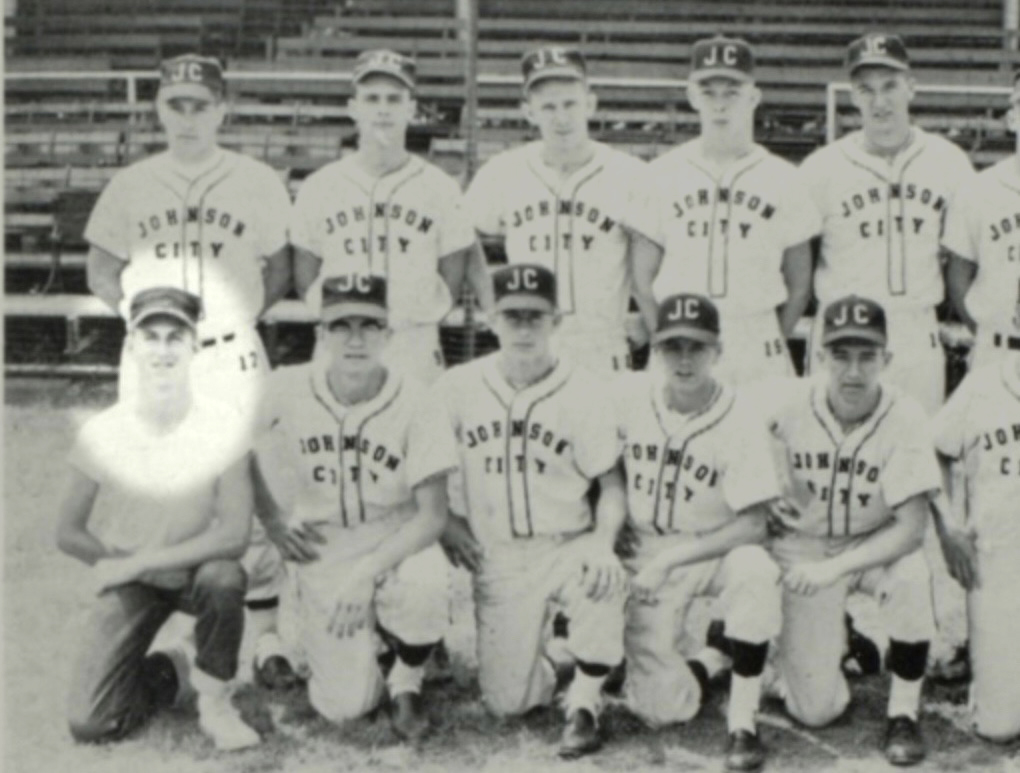

Jerry T. Williams was the manager on Science Hill’s 1961 state tournament baseball team and he managed to remain involved in sports for the remainder of his life.

The colorful character had biscuits and gravy with Johnny Majors and Ray Perkins, power-slammed and pinned professional wrestling manager Jim Cornette and followed lifelong buddy Ken Campbell’s Walters State Senators baseball team to three Junior College World Series in Grand Junction, Colorado.

“Not bad for an ole Keystone boy,” Williams, who died Aug. 1 at the age of 80, would occasionally note with a smile.

Williams was the principal for 28 years at Morristown East, where he also spent 17 seasons as an assistant baseball coach.

Campbell, who started on Science Hill’s 1961 state tournament baseball team, grew up with Williams in Keystone. Williams traveled across the South and beyond to watch Campbell-coached Walters State, which won the junior college national championship in 2006.

“He was my number one fan,” Campbell said. “Jerry and Bonnie (Williams’ wife) just traveled everywhere we went and they were enjoyable to be around.”

Campbell’s brother Jack was the president at Walters State when Campbell coached. More than 40 years earlier, Jack coached Keystone Presbyterian Church to an undefeated basketball season when Campbell and Williams were teammates.

“Jack coached us,” Campbell said. “At the time, he coached basketball over at Ross Robinson in Kingsport and then the next year he coached the ‘B Team’ at Kingsport High School (Dobyns-Bennett). And he was coaching us in the church league, and we went undefeated. We had a lot of fun.”

Williams and Campbell were friends as long as Campbell can remember.

“The thing about it is, if you were Jerry’s friend, he always wanted to talk about Keystone,” Campbell said. “Back then Keystone had the reputation of being the meanest community in Johnson City. And he loved talking about that and, you know, just how all us boys got out of there, and through hard work, made something out of ourselves.

“And here Jerry, being a principal, he touched so many kids’ lives. And I think just growing up in Keystone had something to do with all that.”

Williams, who had a huge turnout for a memorial service at Morristown East, was hands-on with the East athletic department. He was sometimes referred to as the “athletics principal” and attended all but two Morristown East football games in 31 seasons (1973-2003).

The East player he discussed most frequently was quarterback Randy Sanders (class of ‘84), who went on to be the offensive coordinator at Tennessee when it won the national championship in 1998 and head coach at East Tennessee State when it won a Southern Conference title and beat Vanderbilt.

“Jerry had a passion for kids, you know, helping young people,” said Sanders, who was a pallbearer at Williams’ graveside service in Johnson City on Monday. “And he was very genuine. He was always the same – always the same. And that resonated very well with some people, and other people it rubbed the wrong way, it seemed like.

“But, you know, that’s the way it goes. I know there’s a lot of people I rubbed the wrong way. It is what it is. I just tried to be who I am. I learned a lot of that from him, just watching him and how he ran the school.”

When it came to Sanders, Williams ran things with a long leash.

“My senior year, one of the girls there at school, it was her birthday,” Sanders said. “So I went and checked her out of class and took the school van and took her to breakfast. And when we finished breakfast at the restaurant, the van wouldn’t crank. So I had to call somebody to come pick us up so we can get back to school.

“And nothing ever came out of it. I never said anything to Jerry, that I was gonna take the van and go check her out of class. I just did it. None of the teachers ever said anything. So it was a little different time, obviously, and you could do a few things and get away with it that you couldn’t get away with now.”

Williams chuckled more than once talking about adventures involving Sanders, who occasionally ran errands for himself and Williams during school hours. He said Sanders was a good student and brought a lot of attention to the school, and Williams had no problem with ruling on a sliding scale.

“One time right before my senior year of high school I had been working out,” Sanders said, “and Jerry came up and we started talking, and he asked me, ‘So what are you doing tomorrow?’ I said, ‘Nothing. I don’t have workouts tomorrow.’ He said, ‘Well, I need you here about 7:30 in the morning. I need you to do something for me.’

“So I got over there and he had me drive the cheerleading team to Boone, North Carolina to cheerleading camp in a van. It’s probably not that often that you have a high school senior drive the cheerleading team off to cheerleading camp.”

There was, at least, a chaperone of sorts. Sanders’ girlfriend was one of the cheerleaders.

Sanders also played baseball at East when Williams was an assistant under Richard Price.

“We used to make baseball trips to Florida,” Sanders said. “And it was always fun. You always knew who was in charge. Jerry and Coach Price were always in charge of things, but we had a good time, you know, and probably did some things on those trips that you couldn’t get away with anymore.”

Sanders wasn’t a star on the diamond.

“Randy’s a good athlete,” Williams said. “That doesn’t mean you could play every sport. Steve Spurrier was a great athlete. He could play anything.

“Randy wasn’t a great baseball player. I don’t even know if he was a good baseball player. But we filled in when we could with him. He played first base. But I tell you why we wanted to keep him: he was great with the other players. He was a leader.”

Sanders’ talent matched his leadership skills on a football field.

“Randy back there was usually worth a touchdown or two,” Williams said. “He had an arm on him. Randy was pretty much on the field a hundred percent of the time. When you went to watch East you always felt like you had a chance to win because you had Randy at quarterback.”

Numerous college coaches visited Morristown, including Alabama head coach Ray Perkins and Tennessee’s Johnny Majors. Walt Harris, then an assistant at UT, initially recruited Sanders for the Vols.

“Walt would always come to my office and sit and talk,” Williams said. “He said, ‘Jerry, what do you think are the chances of Randy coming to UT?’ I said, ‘I’ll tell you what you’ve gotta do, Walt.’ I told him about the Alabama coach coming up and I said, ‘I think if you want Randy to go to UT, you’re gonna have to get Johnny Majors up here to visit him.’ I said, ‘You bring him up here and we’ll have a big country breakfast for him.’”

Majors seemed eager to come and hopefully close the deal – until that morning, at least.

“We set the date and damned if it didn’t snow the night before,” Williams said. “I think Johnny lived off Kingston Pike, but it was down below the road. Walt said, ‘I don’t know if Johnny can get out of his driveway or not.’ I said, ‘Well, let’s put it this way: we’re gonna have the breakfast and it’s up to you to get him up here.’

“And we’re sitting there and in comes Walt Harris and Johnny Majors. Dolly (cafeteria worker) started feeding us. I think we might’ve even had country ham that day. We had everything – jam, jelly, you name it. …

“Walt Harris was from California and Californians don’t know what the hell to do with gravy. So Walt waited to see what Johnny Majors did with it before he took any. And when he saw Johnny put his biscuits down and pour that gravy over it, then Walt took him some gravy and biscuits and he loved it. I’m gonna tell you something … Johnny’s a country boy and he put the food away that morning. We had a great time and it was just like he was one of us. Everybody loved him.”

It was a treasured memory for Williams, primarily, as he said, because Majors enjoyed the visit. Williams had watched Majors play at UT as a reward for being a crossing guard on Roan Street when he was 13.

“I was a Johnny Majors fan ever since I saw him play in 1956 against Dayton when I went down there because I was a patrol boy with the junior high school in Johnson City,” Williams said. “That’s when the end zone had the ole wooden bleachers in ‘em. I’d never been to Knoxville. Just imagine a Keystone boy used to going in Science Hill’s Memorial Stadium and going down there to UT’s stadium.”

After serving in the Army five years, Williams got a degree from East Tennessee State. He took a job at Greeneville, where he was the freshman football and basketball coach four seasons (1969-73).

He then became the assistant principal for three years at Morristown East, a stint that preceded the lengthy stay as principal.

“I started at Greeneville working for Wayne Anthony,” Williams said in 2018. “After him was Roy Gregory. … He went on to coach at Austin Peay.

“I enjoyed it. I lost three football games in four years coaching there. But Roy wanted to do football 26 hours a day. He lived and died football. I told Bonnie, ‘I’m not gonna be a Vince Lombardi. I don’t wanna spend 26 hours a day with Roy Gregory.’ So I’m gonna go into administration.”

After retiring in 2004, Williams became the play-clock operator at Burke-Toney Stadium. He didn’t miss a Morristown East or Morristown West home game from 2004-2022.

A sports writer might have a massive hamburger waiting on him, compliments of Williams, when he entered the press box.

“It’s the Mountain Burger,” he’d say with a smile.

Williams said he missed two Morristown East football games from 1973 through the 2003 season. One was to have lung surgery in 1985 and one was because he attended Tennessee’s football game at Syracuse during the 1998 national championship season.

“I remember him yelling at me from the stands and turning around and waving to him,” Sanders said with a chuckle.

The game was a thriller, although Williams wasn’t thrilled with the venue.

“I was on the end where UT kicked the field goal and won,” Williams said. “I didn’t like that Carrier Dome. I went out the front door and the suction was so bad that I went one way and my UT hat went another.”

David Cutcliffe left for Ole Miss at season’s end and Sanders was the offensive coordinator in the national championship victory against Florida State.

“Everybody in Morristown was excited,” Williams said. “I mean everybody knows Randy. He doesn’t see a stranger. I was jacked up. Here’s Randy, one of my favorites, coaching in the national championship game.

“His mother was so kind and his daddy so supportive of Randy. … They were a good family, and I know all of Morristown was happy when UT beat Florida State.”

When ETSU hired Sanders as head football coach, Williams was quick to weigh in.

“I’ll be surprised if he doesn’t win soon,” Williams said.

Sanders validated Williams’ gut feeling, of course.

Williams died several months after a brain tumor was discovered. The brain tumor brought things full circle.

Williams attended the Lawrenceburg Quarterback Club’s banquet with Sanders in ‘83 when Memphis State coach Rex Dockery, the scheduled speaker, died en route to the banquet in a plane crash.

Williams also had attended the year before with Morristown East coach Carlis Altizer and receiver Toby Pearson, an award finalist in ‘82 who went on to play at Georgia Tech. Charles Greenhill won the award in ‘82, signed with Memphis and had a productive freshman season before dying in the plane crash with Dockery, Memphis State offensive coordinator Chris Faros and pilot Glen Jones.

Sanders easily could have been on the plane.

“Well, it was a twist of fate,” Sanders said. “One of my brother’s youngest son – he was 12 weeks old and it was a week or two before I was supposed to make that visit to Memphis – they found out my nephew had a brain tumor when he was 12 weeks old. So that kind of threw all our plans at that time awry, and my mom took off and she was gone. And it just wasn’t a good time for me to make that official visit.

“So we rescheduled it, or otherwise I would have (been on the plane). That was the plan. I was gonna go make my visit, then fly with him to Lawrenceburg and meet Jerry and Coach Altizer and my dad, and then drive back with them.”

Dockery had coached Morristown East to a state title in 1969 – the inaugural year of the TSSAA playoffs. He was recruiting well at Memphis State, had the Tigers trending up. Sanders was looking forward to the recruiting visit and Williams was excited about hearing Dockery speak.

“We’d eaten and everything and we’re waiting on Dockery to give his speech,” Williams said. “We waited and waited and waited. And Roy Kramer – he was the SEC commissioner – got up finally and told us that there’d be a delay. And then a little later on he said the plane had crashed trying to land. And Rex Dockery got killed, and the Greenhill kid that was player of the year the year before was on there and got killed, too. …

“It was all a heartbreaking experience, especially when Rex Dockery had coached the first (Class AAA) state championship team at Morristown High School.”

The entire ordeal enhanced Sanders’ appreciation of life – and where you stack up in the grand scheme.

“It made you realize God works in his own way,” Sanders said. “And as tragic as it was to find out my nephew had a brain tumor – and at that time they thought it was, you know, that he wouldn’t live very long – he’s still alive today doing fine. He survived a brain tumor. But that’s what ended up keeping me off that plane.”

The brain tumor brought to mind Williams’ nightmarish final few months.

“He was just a really unique person and I regret that I didn’t get to spend more time with him at the end,” Sanders said. “I just retired and got back and we were planning to go to have lunch or go get dinner or something like that, and it seemed like about the time we got connected and we’re getting ready to do it is when he found out he had the brain tumor. So I never got to spend a lot of time, and I regret that.”

Williams’ admiration for Sanders could be heard in his voice. But he could be discussing a custodian or team manager with similar affection. His candor and enthusiasm were endlessly entertaining.

Williams said he “dabbled” in professional wrestling (Smoky Mountain Wrestling) as part of fundraisers. Before he knew it, he said, Jim Cornette was hitting him in the back with a tennis racquet or he was being pinned in the mud by the Chicago Knockers, an appropriately and/or inappropriately named female tag team.

The first night he got in on the act, Williams, wearing a suit and tie, was wailing away on Stan Lane up against the ropes. Enter Cornette, “who started pounding me in the back with his tennis racquet,” Williams said.

Williams said he eventually stole Cornette’s racquet, which may or may not have been part of a plan. Williams said he gave it to a former football manager’s mother years later.

That was almost as much fun, he said, as getting one of the Chicago Knockers in an airplane spin and slamming her into the mud.

“I didn’t know if I could get her above my (shoulders),” he said with a chuckle.

Wrestling memories generated smiles at Williams’ graveside service.

“He just had a natural way about him,” Sanders said. “He could tell stories. He was good with people, was always enjoyable to be around. I don’t have any stories about not enjoying my time with him. You just always enjoyed those times.

“I remember one of his big things he used to always say, he’d be saying something, and if everybody wasn’t listening or paying attention or responding right away, he’d say, ‘Hello wall. I feel like I’m talking to a wall.’ He used to always say that, ‘Hello, wall.’ Yeah. I still pull that one on my wife and my girls every now and then when I’m saying something and they’re not listening.”

Spending his golden years watching Campbell mold Walters State into one of the premier JUCO programs in the country brought Williams a great deal of pride and joy.

“Grand Junction, Colorado was a great place to go,” he said. “I went three times. That (World Series) is what they live for in Grand Junction. …

“Ken talked to me a lot (in Morristown). I’d go in the dugout sometimes. I’d tell him what I thought, and hell, sometimes he’d go with it. … I’d take him to the casino when they played at Dyersburg.”

Williams was remembered fondly on social media by a number of former East students. A common theme was his open-door policy with students from all walks of life.

He was as friendly as ever when his clock-operating days were winding down. He raved about David Crockett’s Prince Kollie one night when Kollie ran wild in Morristown, suddenly throwing out names such as Sanders, James “Little Man” Stewart and Jason Witten.

“I got a check for a thousand dollars in the mail at the end of the first season running the clock,” he said that night. “I didn’t even know I was getting paid. I like doing it because I can still be around people – and that’s what I like.”

Williams sensed his time was near when he was diagnosed with cancer this past spring. His sense of humor, as Campbell can attest, remained sharp right up until his brain failed him.

“Well, Kelly (Williams’ son) called me just as soon as he found out about it,” Campbell said, “and I just called Jerry and told him I was praying for him and if there’s anything I could do to help him, just let me know. And he texts me back and he says, ‘Well, I hope you have a good game of golf today.’ He knew I was going to be playing golf because I play every day, and he said, ‘I hope you have a good game of golf today.’”

Campbell couldn’t help but chuckle at Williams’ nonchalance. Even under grave circumstances, it wasn’t entirely unexpected.

Campbell’s lifelong friend must have said “so long” in some other language the day he died.

“It was kindly funny (odd), you know,” Campbell said, “I was praying for him every night, and I got to thinking, ‘I need to call him again.’ And that morning, you know, Kelly texted me and said he had passed away. It happened fast. … Jerry T. was one of a kind.”