By Jeff Keeling

Keith Treadway has seen Boone Lake’s drawdown, and frequently, from a perspective most Tri-Citians won’t experience. Now, the retired Marine Corps officer and Wings Air Rescue helicopter pilot is set to get a much closer look at one or two very important patches of land exposed by the lowered lake level.

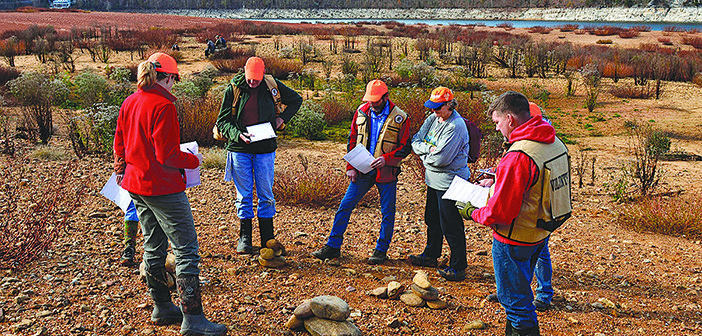

Along with 13 other carefully vetted (background checks included) volunteers, Treadway recently underwent a day of intensive training with Tennessee Valley Authority Archaeologist Erin Pritchard. As the lake remains drawn down for the next several years for repairs at Boone Dam, Treadway and the other volunteers will record baseline data on archaeological sites that are assigned to them, then monitor the sites through the duration of the drawdown.

“It’s really in all of our best interest to try to protect these areas the best that we can, because the professionals really need a chance to get in there and study the area and interpret pre-history, kind of what this area was all about,” Treadway said last week.

Pottery of the Lamar Incised style shared by Cherokees and other ethnic groups and found in the Boone Lake watershed by ETSU researchers. The stone arrow point was found next to it. The shard was dated by luminescence to the mid-1400s. Photo courtesy Jay Franklin.

“If we’re not able to protect that and they’re not able to go in and study and document what they find, we’re going to lose that part of our cultural heritage.”

Pritchard said the local volunteers are the second cadre valleywide of a new TVA program called “A Thousand Eyes.” The agency is responsible for protecting thousands of archaeological sites across its seven-state area from erosion, vandalism and looting. TVA added the Thousand Eyes program to its other archaeological outreach last spring with a pilot run near Huntsville, Ala., where volunteers are now helping monitor Painted Bluff, a well-known native American rock art site.

“With the Boone drawdown, we thought this would be a good area to focus our second training because so many archaeological sites are going to be exposed,” said Pritchard, adding the total probably numbers “several dozen.”

Volunteers in Gray spent classroom time learning about archaeology, regional cultural history and federal preservation laws. One important fact is that most protection applies only to public land. Human burial sites are the only thing private landowners are legally bound to protect – though Pritchard and a fellow archaeologist, East Tennessee State University professor Jay Franklin, both said many private landowners work with professionals to extend preservation efforts to their land.

A day of fieldwork followed, teaching volunteers how to detect damage at an archaeological site.

“It was a very good group,” Pritchard said, adding that the 14 were selected from more than 40 applicants. “We’re very excited to have a passionate group of people that are excited about going out and protecting these resources.”

As with sites around Northeast Tennessee that haven’t spent decades covered by artificial lakes, the sites along the Watauga and Holston rivers and their feeder creeks, which comprise Boone Lake, include a mix of Native American and European artifacts.

“There are lots of prehistoric sites out there, which would have flakes and projectile points and pottery, all the way through historic sites, which would be early European settlers that came in,” Pritchard said. “It might be house foundations, storage ceramics, glass, nails, things like that.”

As such, TVA works with like-minded groups including federally recognized tribes who, Pritchard said, “have a lot of interest in the protection of those resources on their ancestral land.”

It’s all enough to have gotten Treadway, “waiting on my marching orders and rarin’ to go.”

An amateur historian with deep family roots in the area, Treadway said he stumbled across the TVA program as a result of some recent studies.

He had been simultaneously reading books about Hernando Desoto and Juan Pardo, two Spanish explorers who made their way inland from the Carolina coast to and over the Appalachians in the mid and late 1500s. Treadway came across the Tennessee Council for Archaeology’s website, which in turn led him through various links to his discovery of the Thousand Eyes program.

“Flying over this area has given me I think a unique perspective,” Treadway said. “Some of the areas that were possibilities for Juan Pardo and Desoto and the way they came into and over the mountains, I occasionally will look down and think, ‘yeah, that’s plausible and feasible and interesting.’”

Just as interesting now for Treadway is his work that will take place on terra firma. He’ll be assigned one or two sites, and after collecting baseline data, will revisit on a regular basis and record any changes, Pritchard said.

Treadway and his colleagues will, “be looking for things like vandalism, artifact removal, digging, littering. Any sorts of activity that may have an impact on that resource, they’ll report back to TVA,” she said.

With site protection her primary role with TVA, the drawdown produces an equal mixture of excitement and stress for Pritchard. “You’re getting to see archaeological resources that aren’t always visible, but with so many resources exposed, with protecting those sites part of my job description, I have to worry about that and the fact that so many other people, in some cases bad people, have access to those sites now, too.”

Nonetheless, she said, “we’re going to survey some more TVA land and private land while the water is drawn down, and we are working with ETSU to do some of that. We’re also working with some of the Cherokee tribes to do some research projects on those sites.”

For his part, Treadway anticipates getting more informed about any surveys that do occur. His understanding is that this area hadn’t received much attention from archaeologists when the TVA lakes were created. That’s changed as ETSU’s Franklin has led an increasing number of archaeological surveys in the area in recent years.

“What got me into the program is just giving them (professional archaeologists) a chance to really document and study the area,” Treadway said. “There’s a finite amount of time before the water’s going to be back up in the lake, and they’re not going to be able to look at the area like they are now.”

Pritchard said the sites Treadway and his fellow volunteers will help protect are invaluable.

“They’re part of our collective American heritage, and archaeologists protect these sites so that one day down the road we can learn more about that heritage by studying those sites. When they’re destroyed from looting activity, that information potential is gone, and lost forever.”