By Trey Williams

Johnny Russaw is certain to get a wonderful reception on Saturday at East Tennessee State, but as far as he’s concerned, his playing career fell incomplete.

Russaw, ETSU’s first African-American scholarship football player, will be recognized at the Buccaneers’ football game Saturday against Wofford along with Tommy Woods, who arrived at ETSU a year before Russaw in 1963 to play basketball.

They’re being recognized as part of the unveiling of the Woods-Russaw Trailblazer Award, which will be given annually to a former ETSU student-athlete for his/her historic accomplishments.

Woods, an Alcoa native, could’ve gone to Texas Western, where he would’ve been on the national championship team in 1966 – the team that inspired “Glory Road”. He occasionally regretted not going to El Paso during his first two rocky years breaking the color barrier at ETSU.

Russaw, a football and basketball standout at Johnson City’s Langston High School, occasionally regretted not going somewhere such as Tennessee State during his final two years at ETSU.

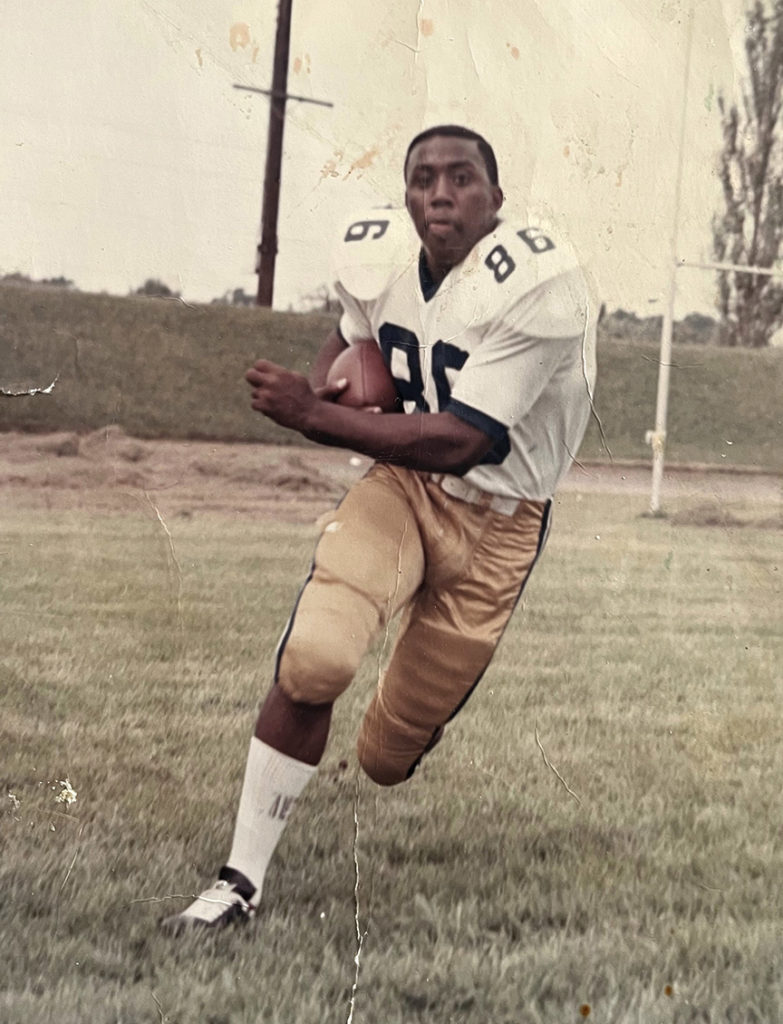

Russaw hit the ground running at ETSU. He had 85 all-purpose yards in the Blue-Gold game his freshman season. He had a team-high 291 receiving yards as a freshman, and his 14 receptions were six less than the program’s single-season record.

And Russaw had two touchdown receptions, which were one less than team leader Wayne Waff, who was signed by San Diego following the 1965 season.

Russaw was ETSU’s leading returning receiver in 1966 as a sophomore, and his two-year receiving yardage total (591) was higher than Waff’s (584). The Dallas Cowboys talked to him after his sophomore season and he was offered a chance with San Diego’s “farm team” in Montreal following his senior season.

“The contract was like $75 a game and $25 for this and $25 for that,” Russaw said. “No medical insurance.”

Although it was an offer he could — and would — refuse, it was validation for Russaw, who was essentially relegated to punter as an upperclassman at ETSU. Granted, he was a good punter. He was second in the Ohio Valley Conference with a 41.1 average on 45 kicks as a sophomore and sixth in the nation at one point.

But coach Star Wood resigned and John Robert Bell left Georgia Tech to succeed him prior to Russaw’s junior season, and Russaw’s punting average apparently impressed Bell more than Bell’s receivers evaluation impressed Russaw.

After all, Russaw had recorded a productive first two seasons – the best freshman-sophomore start ever by an ETSU receiver. And even after his senior season, Russaw was recognized in most improbable fashion for a TD reception against Middle Tennessee State. A full-page picture of Russaw going up for a jump-ball against the Blue Raiders’ Mike Jones was used as the back cover for the 1968 NCAA Collegiate Football Record Book (season preview media guide). Florida State’s Ron Sellers was on the cover.

The inside page reads, “Outside Back Cover: East Tennessee end John Russaw has inside track in pass-grabbing duel with Middle Tennessee’s Mike Jones, netting him 46-yard TD.”

It was a feather in Russaw’s cap, albeit in ironic fashion.

“I think he (Bell) was trying to put in this other boy he’d brought with him,” Russaw said. “And to me, it was a joke. If he would’ve been anywhere near what I could’ve did – and what I did when I was a receiver – I wouldn’t have had no problem. I always said, ‘If you were better than me, then I’m supposed to be over there on the sidelines.’”

Russaw got in the game with the outcome long decided in the final game of his career, a blowout win at Austin Peay. And he caught a TD pass from backup quarterback Bobby Meade – a hollow score.

“After (my career) it seemed like John Bell tried to be my friend and everything,” Russaw said. “And we’d talk and do things, but I just couldn’t get that out of the back of my mind. Why? It was never explained to me why that he kept me over there like he did.

“If he had a tough situation that’s when they’d try to stick me in. When they’d stick me in the other team would holler, ‘Back up. Back up. Russaw.’ That’s what they’d start hollering. So I mean they knew.”

Russaw once read Bell being quoted about how Russaw was such a solid punter that it was how he could best help the team.

“He said, ‘He could use me best at the kicking position,’” Russaw said. “I said (to myself), ‘Yes, on fourth down.’”

And perhaps due, in part, to Russaw’s limited opportunities on offense, the Bucs punted often. He holds ETSU’s single-game record for punts (14) and his 79 punts in ‘67 are the second-most in program history.

Among other schools, he could’ve attended Tennessee State (Tennessee A&I) or North Carolina A&T in Greensboro.

“Really, that’s where I wanted to go – to a black school,” Russaw said. “I knew nothing about white schools but watching them on TV. Back in the day, you couldn’t hardly even go to a Science Hill game. You couldn’t get in those games until later on just like you couldn’t go to nothing else – the movie theaters. The Tennessee Theater, you was upstairs and they was downstairs.”

It was more of the same in the early going at ETSU.

“You could tell at first there wasn’t anybody gonna eat with me in the cafeteria,” Russaw said. “I generally sat by myself.”

Walk-on Jimmy Jordan was an African-American football player from Alcoa, but Russaw didn’t recall him getting to eat at the training table.

“We had a training table in the cafeteria, a section that was closed off with the sliding glass doors,” Russaw said. “There just wasn’t no social life for ya out there. There was no social life. For a social life you had to go back across town, go back up on the Hill (Tannery Knobs).

“It was like – you were just there (at ETSU). You’d walk across campus and people probably knew who you were, but they wouldn’t say nothing to ya. You know, you just had to suck it up.”

It was a jarring transition for a 19-year-old accustomed to being the big man on campus – a black campus at that. Langston played football on Thursday nights at Memorial Stadium. Russaw started at quarterback as a sophomore and junior and moved to halfback when his brother Gene played quarterback his senior season.

Langston went 20-2-2 during Johnny Russaw’s final three seasons. He led the Golden Tigers, which included powerful fullback Kenny Hamilton, with 59 points during their 6-1-1 season his senior year.

The 6-foot, 190-pound Russaw shined on the hardwood, too. Langston averaged over 100 points per game while going 24-6 his senior season.

Douglass (Kingsport) exited unannounced at halftime while trailing 54-15 during Russaw’s junior year. Russaw recalled official Charles McConnell asking someone to go tell Douglass it was time for the second half, but there was no one in the locker room to alert.

“They said their coach said that we weren’t running no hundred up on them,” a chuckling Russaw said. “We were clocking everybody that year.”

The 6-foot-3, 230-pound Hamilton scored 85 points in a game against Tanner (Newport) during his sophomore season.

“Kenny was close to 230 pounds and about 6-3 – and a little over maybe,” Russaw said. “Every time I look at Charles Barkley I think of Kenny Hamilton. They had that same look and same mentality.

“You didn’t mess with Kenny Hamilton. You mess with Kenny, he would hurt you.”

Russaw could leave a mark, too. He made a sudden impact on the opening kickoff in a game against Riverside in Chattanooga’s Engel Stadium.

“This was against Riverside their first game,” Russaw said. “It ended up in a tie. They were getting a lot of players from Howard High School.

“I did all the kicking and I was quarterbacking. I kicked that ball off and that boy caught the ball near the goal line and I hit him and that boy was out of the game. I think I might’ve broken his leg or something. So they were after me, and this ole boy – he cut me down from behind.”

And before he knew it Russaw was ready to stomp the yard, so to speak, for his Langston fraternity.

“The guy cut me from behind and I was up in the air,” Russaw said. “And I come down and I put my feet on him about two or three times. And the ref came over and grabbed me and took me out of the game.”

Break the leg of a player in Chattanooga or Big Stone Gap, Virginia, Russaw suggests, and they might be able to get medical attention at the V.A. Russaw said some of those teams surely had players closer to 25 than 18.

“Man, we got down there one night (against Booker T. Washington), we thought it was geriatric night,” Russaw said through laughter. “Kenny Hamilton was there. We went to the assembly when we got off the bus down there. Boy, they was all sitting there waiting on that bus. They jumped on us talking about, ‘All these guys have come out of the mountains’ and we’re gonna do this and we’re gonna do that.

“And I got up and I said, ‘We’ll see. We ain’t scared of nobody down here.’ And the ole boy got up and said (rather comically), ‘We ain’t neither! We ain’t neither!’ I said, ‘Well, we’re gonna see what happens tonight.’

“So them old guys come out there, and we hurt ‘em bad. We were putting the licks to ‘em.”

Russaw and Hamilton, who signed with ETSU in basketball, had a number of college options for football and basketball.

The late Columbus “Teddy” Hartsaw was a star at Langston decades before Russaw. In 2005, Hartsaw still regretted Russaw having elected to integrate the ETSU football program as opposed to signing with an African-American school.

“Johnny and Kenny Hamilton both made a mistake when they went out to State,” Hartsaw said. “They didn’t play them. A pro scout looked at Johnny his first year there and told him he was the best player on the team.

“It wasn’t just the coaches. When Johnny was playing, I can remember he would be out there in the clear waving his arms and the quarterback would throw it in a crowd of guys instead.”

Russaw grew up watching Langston heroes such as Billy Gene Williams, who went on to start at quarterback as a freshman at Dillard University in New Orleans. When he was 11-12 years old, Russaw dreamed of emulating Williams – and he reached his goal.

“Johnny ran the show in football and basketball,” the late Hamilton said in 2005.

ETSU took note. Buccaneers assistant coaches Pete Wilson and Paul O’Brien attended Russaw’s historic Feb. 1, 1963 signing along with Langston basketball/football coach Paul Christman.

“It sort of shocked me when my coach (Christman) came up and said, ‘Mr. Johnny, the ETSU coaches have called me and they’re interested in offering you a scholarship,’” Russaw said. “And there was a lot of good players around here at the time I was playing. Morristown had some good black players. Slater and all those had some good players.

“But I was always on the radar as far as football and basketball. The coach (Madison Brooks) asked me if I would like to play basketball at ETSU. And I said yea until I’d gotten beat around in football all year.”

Numerous people have said Hamilton could’ve started in football at ETSU and Russaw could’ve started in basketball. But along with the wear on his body, Russaw was concerned about the two-sport grind making academics more difficult.

The late Wayne Miller, who played basketball at ETSU when Hamilton was there, said Russaw would’ve definitely helped the Bucs on the court. Miller was an avid spectator at some Langston games.

“Bobby Wilburn was probably the best shooter on those Langston teams,” Miller said. “And Kenny could rebound at one end and fill the lane on the other. But I believe Johnny Russaw was the best all-around basketball player.

“Johnny could jump and run. He ran the show for Langston. And believe me, it was quite a show.”

Russaw must’ve felt like he was starring in a horror show his freshman season at ETSU. It was perhaps his first week on campus when he entered the dorm and a teammate knocked the wind out of him by sucker-punching him in the gut.

“I came in and was getting ready to go in my room and all the sudden a door opened,” Russaw said. “I turned around and it was a lick to the stomach.”

And Russaw was blasted by a blindside in what was essentially a walk-through without pads. So much for “teammates.”

Of course, coaches could blindside him, too. He didn’t receive the Most Improved Player trophy at the end of his freshman year, which wouldn’t have been nearly as disappointing had a coach not told him a week earlier that he was getting it.

“Pete Wilson came up and told me before the athletic banquet, ‘John, you’ll be getting the trophy for Most Improved Player,’” Russaw said. “About a week before the banquet he came up and told me, he said, ‘John, we decided to give this trophy to Larry Watson since he’s a graduating senior.’ I’d done told all my people I was getting it. He said, ‘You’ll be getting plenty of trophies while you’re here.’”

Not that Russaw had a problem with Larry Watson – or his brother Darrell. Indeed, Russaw saw the Watsons and people such as Miller, fellow basketball player Gary Martin, Pat Carter and trainer Jerry Robertson as ambassadors for decency. They helped make his school of hard knocks more bearable in the early going.

“We had some pretty good guys there,” Russaw said. “There wasn’t a whole lot of in-my-face stuff. But you’d hear words in the dorm and you’d know where it was coming from.

“I think the whole thing was I hadn’t played with white guys and white guys hadn’t played with me. Plus, some of the guys were from Georgia and all that.”

Russaw did make a number of good memories while blazing a traumatic trail. Oddly enough, one of his favorites is a brawl – between ETSU and Eastern Kentucky at the end of the first half.

“A fight broke out and Leroy (Gray) and Ron Overbay and all of ‘em were across the field, and here we all went over,” Russaw said. “So state troopers came across. We were over there duking around and carrying on. They broke it up and we walked back across the field and Booney Vance was sitting there with his legs crossed and his arms crossed, and one of the boys said, ‘Booney, where was you at?’ And Booney says, ‘Boys, there ain’t nothing in my contract that says something about fighting.’

“That tickled me to death. If you saw Booney Vance, you wouldn’t hardly think he was a football player. He was gentle-like.”

Vance went on to become a doctor. Russaw was a smooth operator with a razor, and he cut a number of players’ hair in college, a practice he’d started in high school.

“That’s how I made my money when I was in high school,” he said. “None of the black barbers I knew around Johnson City had a license. I cut hair all the time in high school. I did pretty good. At first I was getting a quarter a head.

“And Tommy Woods and Butch (Larry Woods) will tell ya, I kept all their heads cut out there in college. I was the barber. I’d cut theirs and some of the white guys’ hair.”

How much did the college guys pay him?

“They paid me no attention,” Russaw said with a chuckle.

The Citadel paid special attention to Russaw when ETSU visited Charleston, South Carolina during his junior season.

“I think I got blasted more over at The Citadel than at my school, you know – cursing me out, calling me names to my face,” he said. “And the coach, he didn’t say nothing to ‘em over there. You’d get hit on the sideline over and there was all this ‘black MF’ and ‘you son of a’ and all that stuff. That’s when they threw the drink on me.”

Russaw said The Citadel initially threatened to cancel the game if he played.

“They didn’t want me to stay in a motel,” Russaw said. “The (ETSU) coaches told ‘em if I couldn’t stay we wouldn’t be playing over there.”

Money might’ve trumped bigotry.

“I was novelty at that time,” Russaw said. “I guess it was about a sellout and they didn’t want to say, ‘Don’t come over.’ That stadium was packed.”

Russaw, 76, isn’t bitter. He’s a happy soul, in fact. Active in church and retired from the TVA, Russaw has a loving wife (Carlette) and three successful children (Andrea Wilkerson, Shea Wilkerson, Kesha Russaw).

Russaw said he was raised by his grandmother, Bertha Russaw (his mother died when he was young), to treat people the way he’d want to be treated. He wasn’t going to let hate steal his joy and pride.

Initially, it looked like he’d live in New York with Bertha and her daughter. But Bertha was ready to come back to Johnson City after a year, and they returned to Tennessee when Johnny finished first grade in Brooklyn.

“My mother died when she was 42 years old and my grandmother was always in my life,” Russaw said. “She’s always been mama. She was the type that had values that you’d wanna follow anywhere.”

Being a black woman born late in the 19th century with little education and living in the rural South wasn’t going to slow Bertha, Russaw suggests.

“She was out of Marion, North Carolina,” he said. “She’d tell me how they had to work mules and they’d have to go places where they were scared men was gonna jump on ‘em because they had to go a long way to do stuff.”

Russaw said Coach Christman, a Langston alum who was shot in Europe in World War II, was another lesson in toughness, a father figure and an excellent coach.

“I think what made him so successful was he not only cared about the team (players),” Russaw said, “but he knew the sports and had played the sports. He knew what he had to do to win, especially with the players he had.

“He’d get out there and run with ya. We were out there scrimmaging one time and he was out there – he was always in his shorts with the whistle – and we’d hand off that ball to him and you could hardly touch him. That’s when I was young, probably the eighth or ninth grade. They said he was an excellent ballplayer.”

Christman tried to prepare Russaw for what he’d be up against if he went to ETSU – not that Christman was trying to discourage him. Christman, it’s been said, thought Russaw had the makeup to withstand the adversity.

“Before I went there he said, ‘Mister Johnny, I’m gonna tell you before you go, you’re gonna have to be three times better than almost their worst player to play,’” Christman said. “He said, ‘A lot’s gonna go on that you ain’t used to going on.’ And he sort of talked to me, and he said, ‘Just be prepared.’ He said, ‘You’re the pioneer of what’s gonna be happening out there.’”

And 57 years after being the first African-American player at ETSU and the first African-American to play against Wofford, Russaw will be out for the coin toss when the Bucs host Wofford on Saturday. Russaw was excited about ETSU’s season-opening win at Vanderbilt and perhaps even more excited about its Southern Conference-opening overtime win at Samford last week, and he’s excited about hopefully helping inspire the Bucs against the Terriers while perhaps receiving a sense of completion.