By Trey Williams

Stuart “Plowboy” Farmer, believe it or not, wasn’t a country boy. He grew up in Chattanooga.

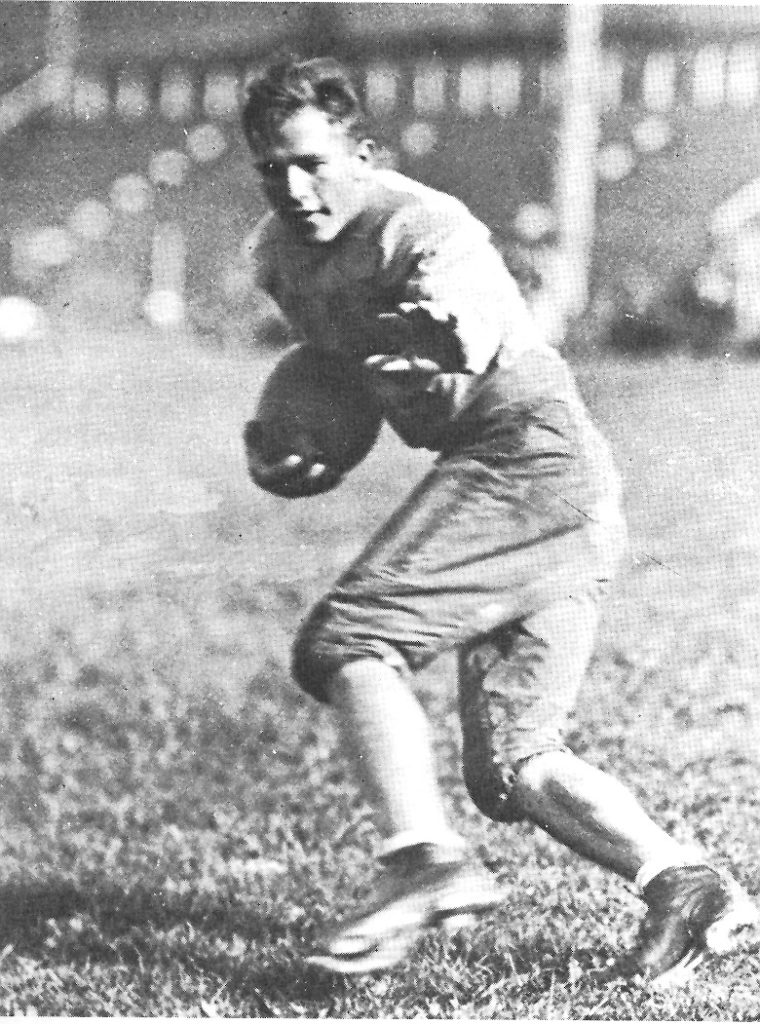

The man that put Science Hill football on the map in the 1930s got his nickname as a determined, leg-churning running back. The 5-foot-10, 145-pounder was a two-time all-conference halfback for Johnson City native W.S. “Pedie” Jackson at Emory & Henry in the late 1920s.

Farmer was fresh out of college when he took over at Science Hill as a 23-year-old in May of 1930. He inherited a program that had sputtered to a 33-48-12 record since its inception in 1919.

But Farmer turned the Hilltoppers around on a dime. With skill players such as Jack Osborne, Kermit Tipton, Charlie, Fleming, Red Latteral and Vincent Darden, he compiled an 84-37-7 record in 12 seasons despite beefing up the schedule.

His teams produced two unbeaten seasons, two mythical state titles and a 26-game stretch without a loss. Farmer’s 1939-40 teams, which included Osborne, Tipton, Darden and linemen such as Arthur “Bud” Kelsey, Harry “Red” Caughron and Bob Storie, outscored opponents 485-46 while going 20-1-1.

Science Hill’s defense gave up seven points during the 1939 season, which included a scoreless tie against Bobby Cifers-led Dobyns-Bennett. Cifers led the nation in scoring in 1938 (235 points) and ’39 (164 points) and played four years in the NFL after a College Football Hall of Fame career at Tennessee.

But he was held to less than three yards per carry during the scoreless game in Johnson City. Farmer’s Hilltopperswere well prepared and fired-up.

“Cifers was a good back, but when the ball got to him we were there,” the late Kelsey said in 2011. “He’d get caught about the time he got the ball.”

Cifers had scored seven TDs in four games prior to being shut down by Science Hill, including two apiece against Chattanooga and Louisville Manual, the mythical national champion in 1938.

“Kingsport had a hard time believing we could stop Bobby Cifers, even after we’d done it,” Kelsey said.

Farmer’s teams were fundamentally sound and physical.

“Farmer was on my butt all of the time,” Kelsey said. “He was a disciplinarian. He didn’t take any crap off of you. Farmer admired rough and tough football.”

Farmer also excelled at basketball and track in high school and college. He played on Chattanooga Central’s state championship basketball team in high school in 1925. The team advanced to play in a national tournament in Chicago, which four years later, ended up costing him his senior year of basketball eligibility at Emory & Henry.

Farmer coached Science Hill basketball five years (61-32) and led the ’Toppers to a state track title when they had Charlie Fleming running in 1935.

Science Hill’s 1932-33 football teams went undefeated, outscoring opponents 294-48 in ’33. The Hilltoppersshut out Knox Central and had little trouble defeating Elizabethton (33-0), Dobyns-Bennett (19-6) and Chattanooga Central (33-16).

Elizabethton staged Farmer’s mock funeral prior to a 1940 matchup in Elizabethton.

The Cyclones were coached by Niles “Mule” Brown, who was later the head coach at Science Hill (1948-54). Brown couldn’t have envisioned such a move after the 1940 game, which Science Hill won, 31-0.

Jack Osborne ran wild. The pregame festivities in Elizabethton, which included a hearse, had left Osborne dead serious about winning.

“It upset Coach Farmer,” the late Osborne said in 2007. “He didn’t cry but he had tears in his eyes. And seeing that, it upset me so much I got the opening kickoff and took the cotton-picking thing 91 yards for a touchdown. And the next time I got my hands on the ball, I took it 70-some yards for a touchdown. My point is that Farmer influenced me that much with those tears.”

Farmer was ahead of his time.

“He stayed on top of you year-round,” Osborne said. “He’d make sure we had school equipment to play (sandlot) ball in the summer. He wanted us to stay in shape.”

World War II interrupted Farmer’s run at Science Hill. He was in the military for four years beginning in ’42.

He returned to Science Hill for two struggling seasons in 1946-47 before abruptly leaving for Lee Edwards (Asheville) in the spring of ’48.

“I had to put on the first state track meet that I ever saw,” the late Sidney Smallwood, a longtime Science Hill coach and athletic director, said in 2007. “I was working with Coach Farmer at the time. He left to go to Asheville. So they told me I was putting on the state meet.”

To be clear, Smallwood respected Farmer, although he was a burr in Smallwood’s saddle more than once. Science Hill defeated Jonesboro when Smallwood played for the Tigers in the 1930s.

“It was just our luck that those were the years of some of Farmer’s greatest teams,” said Smallwood, who played with Charlie Fleming in college. “Charlie was a very good back.”

Farmer noted in a statement to reporters that he was leaving for a 12-month job in Asheville that was essentially a promotion: “I shall leave Johnson City with a feeling of regret. For nearly 18 years Johnson City has been ‘home’ to me. … Many of the boys on some of my earlier teams have taken positions of responsibility in the athletic and business worlds.”

Caughron went on to be an All-American at William & Mary and a Hall of Fame high school football coach in Virginia.

“Plowboy taught me a lot of good fundamental football,” said Caughron, who wasn’t a screamer or cusser. “I probably had a better fundamental experience in high school than a lot of my William & Mary teammates. Plowboy was quiet but determined.”

When Farmer left Science Hill for Lee Edwards, he took Erwin head coach Cap Isbill with him. They started from the ground up, going 1-8-1 in ’48. But respective 7-2-1 and 7-4 records followed.

Farmer stepped down following a losing season in ’51, but remained on the faculty there until his untimely death in 1955. He was 47.

Farmer was intelligent and, relative to the context of his livelihood, rather refined. An avid fisherman, he wasn’t loud and never acquired any taste for limelight.

But a couple of his Science Hill players suggested he might’ve died from too much living. The cause of death was listed as kidney failure.

In one interview, Kelsey noted how Farmer delighted in defeating Appalachia (Virginia).

“I believe there must have been something between Farmer and the coach up there,” said Kelsey, who noted Appalachia fielding a number of “long-bearded” players. “It was probably over a woman or liquor. Farmer said he’d rather beat them than anybody on the schedule. And he wasn’t one to pick out favorites to beat.”

Tipton was an All-Big Five quarterback for Farmer, and went on to move past Farmer at the top of Science Hill football coaches’ list for winning percentage (74-32-5 from 1956-66).

“I picked up several aspects of his coaching that I liked and tried to expand on,” Tipton said in 2010. “Farmer was tough to play under. He didn’t stand for any foolishness or anything. He was a great coach.”

The Science Hill football program’s most coveted annual award is the Plowboy Farmer Award. It was started, along with a scholarship, by a number of his former players the year he died.

Farmer made an impression on Asheville Citizen-Times sportswriter Bob Terrell.

“He’d put a football team through a practice with such ease that onlookers often didn’t know he was around,” Terrell wrote after Farmer’s death. “That’s how unnoticed he went in a crowd. He was never a showboat, never one to attract unnecessary attention. He tried to drill his team as thoroughly as possible without undue strain on anyone.”

Isbill succeeded Farmer at Lee Edwards.

“I always had a lot of respect for him when I was playing against his teams,” Isbill told Terrell. “But I had a lot more respect for him when I was coaching with him. He was that type of man – you couldn’t help but respect him.”