By Trey Williams

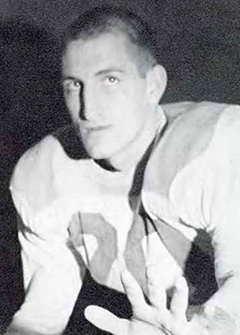

His teammates would tell you that Bob May seemed like a man’s man even when he was a young teen.

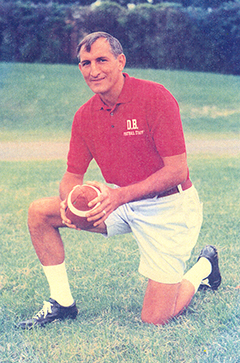

After playing football at Science Hill, Bacone College (Oklahoma) and East Tennessee State, May went on to help mold many men while coaching parts of five decades at Science Hill, Dobyns-Bennett and North Junior High.

For his dedication, May, who coached the 1988 Science Hill football team to a Big 10 Conference championship and went on to become the mayor of Johnson City, got a street – Bob May Lane – on the Science Hill campus dedicated to him last Saturday.

It’s a fitting finish for a man who paved the way for others after growing up “dirt poor” without, as he said, many males in his family setting a good example.

But tough conditions produced a rugged football player. May started at tackle and end at Science Hill while playing with the likes of Bo Austin, who went on to play football and baseball at George Washington and was the Most Valuable Player in the 1957 Sun Bowl.

The late Austin would chuckle warmly describing one example of May’s toughness. He said May blocked a kick with his face against Morristown.

“I think he ended up needing 10 to 12 stitches, but he didn’t miss a play,” Austin said. “We were concerned and he kind of (growled), ‘Let’s play football.’ Bob was tough and he wanted to win.”

May said Science Hill assistant football coach Cot Presnell was a significant influence.

“Cot Presnell sure helped me,” May said in 2012. “You could tell he cared about you – him and his brother Zeb.”

May (class of ’53) played for Niles “Mule” Brown at Science Hill. In addition to Austin, the Hilltoppers had players such as “Little” Bob Evans and Bob Taylor. Science Hill was 12-4-3 during May’s final two seasons.

“Bo was a really good fullback,” May said. “And he threw me a (game-winning touchdown pass) against Kingsport my junior year. I couldn’t have missed it. He put it right in my hands from about 25 yards out.

“Bob Evans was probably the best all-around athlete at that time. And we had a star in Bob Taylor.”

May had good speed. In fact, he won 120-yard high hurdles events and 440-yard runs at Science Hill and Bacone, a junior college in Oklahoma. In one JUCO track meet, May scored a team-high 14 points. Along with winning the 440 and the high hurdles, he scored as part of the mile relay team.

May was named the Most Outstanding Player at Bacone as a sophomore. He played end at ETSU for Star Wood for two seasons and played football in the Army (1957-59).

May coached from 1960-68 at North Junior High. Those duties included helping scout for the Hilltoppers of Kermit Tipton and his successor, Bob “Snake” Evans.

May might’ve enjoyed coaching at North more than anything other than watching Gary “Shorty” Adams propel his ‘Toppers to the conference title in 1988. May’s era at North included the first year of integration (1965).

“We had 24 whites, 24 blacks and nobody scored on us,” May said. “We had a great bunch of kids and went 8-0.”

May became good friends with Paul Christman, who’d had an impressive run coaching football and basketball at Langston High School prior to integration.

“Paul and I used to scout for Science Hill when I was the junior high coach,” May said. “He was an excellent football coach and basketball coach who had a big impact (at Science Hill). He had teams down there at Langston — they just beat people to death.”

May enjoyed working with Kermit Tipton and helped during Snake Evans’ first two seasons (1967-68) before going to Dobyns-Bennett for a decade. Evans’ Hilltoppers defeated Dobyns-Bennett both of those years before he left, and beat a Morristown team that included Ken Rucker and Marshall Mills.

“Those first two teams Snake had might’ve been the best two I saw at Science Hill,” May said.

May returned to Science Hill from D-B in 1977 to coach defense for Tommy Hundley, who succeeded Evans that season.

“Tommy was ahead of his time,” May said. “They’re doing things now Tommy was doing in the ’70s.”

May had applied for the job when Hundley was hired. He was passed over a second time when Hundley left prior to the 1983 season. Bald-headed, bug-eating Mike Martin was chosen to follow Hundley.

“He did a good job,” May said. “We ran the wishbone.”

Martin went 24-8 in three seasons, but annoyed administrators and some alumni about as easily as he inspired players. So he left for Sullivan North following the ’85 season and May finally got his hands on the wheel.

The ‘Toppers went 7-3 during May’s first season. They lost three games by a combined 12 points to D-B (10-7), Morristown East (28-24) and Sullivan South (12-7).

May doubted all three of those games would’ve been lost if Anthony Whiteside hadn’t injured a knee. The 6-foot-1, 210-pound Whiteside was generating considerable college interest after leading the league in rushing in ’85. “He was a horse,” May said.

Another stud emerged. Gary “Shorty” Adams. Adams became Science Hill’s all-time leading rusher (3,800 yards) and its first 2,000-yard rusher in a season (2,004) as a senior. He set a record with 51 TDs and was recruited by Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee and Nebraska before opting to play baseball by signing with the Montreal Expos.

Adams led the ‘Toppers to a share of a league title as a senior in ’88, a season that ended with a 21-14 loss to Cherokee in the playoffs.

“We had a holding call about 15 yards behind Gary Adams when he was scoring on a sweep,” May said. “Gary was one of the best, if not the best, I ever saw at Science Hill.”

May persuaded offensive coordinator Keith Lyle to dust off his headset when he was hired.

“I think Keith Lyle was one of the best football coaches in East Tennessee,” May said. “The person I went out and got when I got the job was Keith Lyle, and he stepped out of administration and came back. Of course, Gary Adams, I think, made us both look like great coaches.”

Running back Dana Whiteside played on May’s final two teams. He said May kept things loose.

“He would say, ‘Dana, you are a senior captain and I need you to show the team that we need to be ready to play to the point of knocking down a brick wall,’” Whiteside said. “Then he told me to set the example and knock down the wall. I just stood looking at him, like huh. He said, ‘Do it, knock that wall down, Whiteside.’ I said, ‘I don’t know if I can.’ He said, ‘Okay move. I will show the team.’

“Then he walked up to the wall and began to knock down the wall with his hand as if he was knocking at a door. And then he would say, ‘Gotta be smarter than the other team.’ Everyone would laugh.”

Lyle said May is maroon and gold to the bone.

“When I started in junior high, Coach May and Coach (Emory) Hale had this thing called the ’Topper Creed – a whole page of stuff that a real ’Topper was,” Lyle said. “It was about how you conducted yourself in the way you lived, the way you played and the way you practiced. We called it ‘Living like a ’Topper.’ In fact, we told them not to even drink soft drinks. Train. Eat right. Sleep right. Practice hard. Be a team player. Be a good student. We don’t want you in the principal’s office, and stuff like that.

“At that time, kids took great pride in that. They said it was always about the ’Toppers. And it always has been for Bob.”