By Trey Williams

Ernie Ferrell Bowman hated the Los Angeles Dodgers, he might tell you, more than not being able to enjoy a cold beer by Boone Lake on a hot day due to declining health during his later years.

His Dodgers distaste was never more apparent than when the former San Francisco Giants utility infielder was asked if he felt awkward when he inadvertently spewed champagne on Richard Nixon after the Giants secured a World Series spot by beating L.A. in the third game of a playoff series in 1962.

“No, I didn’t,” Bowman said. “He was wearing blue.”

Bowman, a three-sport standout at Science Hill who died in 2019, would’ve been giddy when the Giants took a 2-1 series lead against the Dodgers on Monday.

Of course, two wins was all that was necessary in ’62. The Dodgers and Giants each went 101-61 during the regular season. L.A. had a four-game lead on Sept. 20.

It was a golden era for the transplanted New York franchises. The Giants had Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal and Orlando Cepeda. The Dodgers had Don Drysdale, Sandy Koufax, Maury Wills and Tommy Davis.

Bowman pinch ran for McCovey during the top of the ninth in Game 3 and the former Science Hill/East Tennessee State sprinter raced home with the tying run on Cepeda’s sacrifice fly. The Giants scored four runs during the frame, erasing a two-run deficit in what was a 6-4 victory.

“I don’t know if I’d ever been happier,” Bowman said when asked about crossing home plate to tie the score.

The elation was exceeded the following week in the World Series when Bowman had all three assists in the ninth inning of Game 4, a Giants victory that evened the series with the New York Yankees. The final out came when Bowman fielded Mickey Mantle’s sharply hit ball at shortstop and threw to second base for the force-out.

It was quite a World Series debut for Bowman.

“When I got in there you might say I was just too scared to be scared,” Bowman said.

Johnson Citians attending Game 4 in New York, Bowman said, included his former ETSU basketball teammate Herb Weaver, former Johnson City mayor Ross Spears, the Wright brothers (Wright’s supermarkets) and Arthur Lady and his American Legion Little League team.

Three games later, Bowman and the Giants were crushed when McCovey lined out to end Game 7. Mays, the previous batter, had delivered a two-out double to put runners at second and third with the Giants trailing, 1-0.

“Willie Mays was the best player ever, period,” Bowman said.

And when the ball rocketed off McCovey’s bat, Bowman was sure Mays was going to score from second and the Giants were going to win the World Series with a 2-1 victory. Instead, Bobby Richardson, who was playing McCovey to pull, took a step or two to his left and snatched Bowman’s dream out of the air.

“I can still hear the crack of McCovey’s bat,” Bowman would say.

Bowman had experienced similar disappointment when he played basketball for Sidney Smallwood at Science Hill. The top-ranked Hilltoppers (26-0) missed 12 of 26 free throws in a 51-50 loss to Memphis Treadwell, a loss that wasn’t complete until Bowman’s buzzer-beater was waved off by official Ralph Stout.

Bowman said he believed the basket should have counted. Bowman’s teammates included Jerry Wolff, Bob Taylor, “Little” Bob Evans and Phil Walters.

Bowman led the ‘Toppers with around 18 points per game. Listed at 5-foot-10, he could dunk easily and won the state in the long jump at Science Hill.

“He wasn’t 6-feet but he could dunk,” said Smallwood, who also coached Bowman in track & field. “Ferrell could high jump well over six feet (despite improper technique).”

The state tournament was played in Vanderbilt’s impressive new Memorial Gym, and Smallwood regretted taking the Hilltoppers to watch Kentucky (Frank Ramsey, Cliff Hagan) and LSU (Bob Pettit) play a one-game playoff for an NCAA Tournament berth the day before the state tournament game.

“I thought it’d be a good time for my boys to see how the game was played at the highest level,” Smallwood said.

Instead, the size of the gym and the roar of the crowd unnerved the Hilltoppers, and they were still tight the following day.

“We missed enough lay-ups in the first half to be ahead quite a bit,” Smallwood said. “I would’ve never wanted to be undefeated again.”

Smallwood might’ve been somewhat of a players’ coach for that era, relatively speaking, but his players were sure to be tough-minded.

“I had a girlfriend named Katie,” Bowman said. “One night we were at Ketron and I drove in under the basket and went down hard. I mean I got my teeth rattled.

“Coach Smallwood came out and asked me if I was alright. I said I wasn’t sure and he said, ‘Get up Katie. You’re not hurt.’”

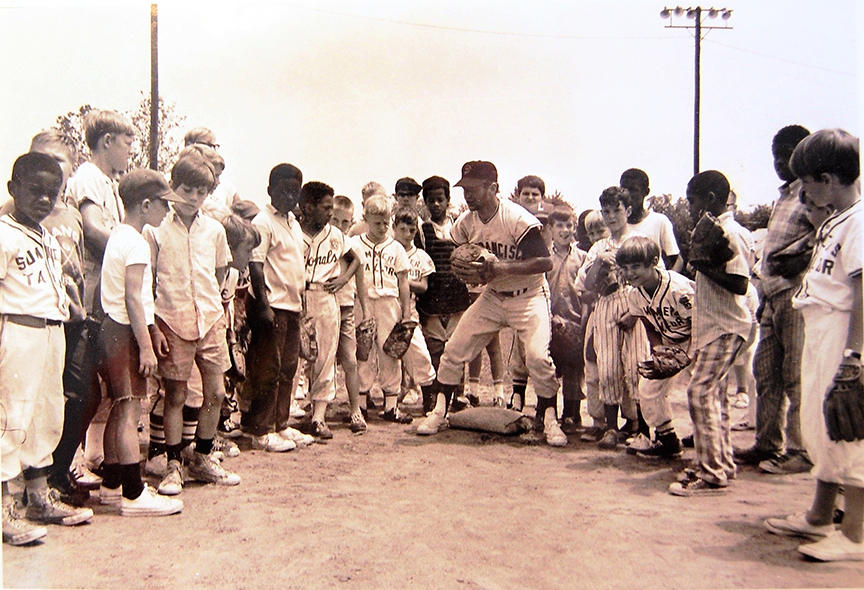

Smallwood was Science Hill’s athletic director when Bowman played for the Giants. Knowing integration was on the horizon, Smallwood asked Bowman to speak at Langston High School, Johnson City’s segregated high school for African-Americans, after his World Series experience with the Giants.

That was not a stretch for Bowman. After all, he grew up within a rock’s throw of the school. Bowman often recalled attending Langston games when he, Pappy Crowe and the referees might’ve been the only whites in the place.

“I remember Coach Smallwood called me,” Bowman said, “and said, ‘You want me to come by and pick you up (for the Langston banquet).’ I said, ‘It’s just three houses down coach.’”

Bowman played against Naismith Hall of Famer Hal Greer while at ETSU. Greer, who played for Marshall, was the first African-American to play for a public school in West Virginia.

“I played against Hal Greer in Johnson City,” Bowman said. “He’d jump-shoot his foul shots.”

Some were wary of Greer. ETSU was still six years away from signing its first African-American (basketball player Tommy Woods). Bowman wanted Greer to be comfortable.

“I went out and shook his hand,” Bowman said. “He just smiled.”

Madison Brooks’ Buccaneers basketball team advanced to the NAIA nationals in Kansas City while Bowman was there in 1956. Bowman said Johnson City Press-Chronicle owner Carl Jones bought him a suit for the trip.

One of Bowman’s favorite memories of playing at ETSU was dunking during warm-ups to excite the crowd prior to a game at Cincinnati. It wasn’t every day you saw a 5-foot-10 guy dunk, some of Bowman’s teammates would say years later, much less a 5-10 caucasian.

“I dunked one during lay-up drills at the field house in Cincinnati and those people went wild,” Bowman said. “Of course, Coach Brooks got on me. We called him ‘Madhouse.’ You were never in better shape than when you played for Coach Brooks.”

Science Hill’s baseball team finished state runner-up when Bowman was a freshman starter in 1951.

“I was petrified,” he said. “(Fifteen) years old and playing second base in the state tournament in Memphis.”

Bowman initially signed to play baseball at Tennessee, where his brother Billy Joe had homered and won two games while helping the Volunteers finish runner-up in the 1951 College World Series.

“When I got to play as a freshman, some of the guys were saying, ‘The only reason you’re getting to play is because of your brother,’” said Ferrell, who played in the ’62 World Series with San Francisco. “I grew up hearing and seeing what a great player he was. I got a baseball scholarship to Tennessee because of Billy Joe.”

But Tennessee football coach Robert Neyland wanted Bowman to return punts. So Bowman returned to Johnson City instead – via a transfer to ETSU.

Oddly enough, Bowman played basketball for the Buccaneers. Baseball coach Jim Mooney wasn’t impressed with his baseball talent.

“I played two games of baseball in college,” Bowman said. “I had three hits and two errors at Appalachian State, and they moved me to first base and I had three hits and an error or two at LMU. Jim Mooney said, ‘You’re a good hitter, but you sure can’t catch your butt.’”

And then Bowman would smile while telling you he went on to become a slick-fielding infielder with a below-average bat. Of course, it was hard to bat playing sporadically, and the starters only seemed to need a day for ailments when someone such as Drysdale, Koufax or Bob Gibson was pitching.

“Jimmy Davenport’s wrist always hurt when Drysdale pitched,” a chuckling Bowman would say.

Bowman concluded his basketball career prematurely to sign with the New York Giants and joined them in Spring Training. Bowman credited former Science Hill basketball coach/Elizabethton Cubs catcher Bill Wilkins for helping his baseball career take root.

“Bill Wilkins just invited me to play for the Abingdon Blues,” Bowman said. “He told (former Science Hill pitcher) Ralph Carrier to tell me. The Blues had Bud Nidiffer, Sid Smithdeal. Bo Austin was playing up there.”

Bowman shined almost immediately, and scouts such as Lefty Lance (New York Yankees), Rex Bowen (Pittsburgh) and Tim Murchison (New York Giants) began taking note.

“All of the sudden five teams were interested,” Bowman said, “thanks to Bill Wilkins.”

Not that Wilkins was the first to spot Bowman’s potential. Johnson City Press-Chronicle owner Carl Jones, the Johnson City Cardinals president, had tried to get his buddy, St. Louis general manager Bing Devine, to sign Bowman.

Jones wanted to offer Ferrell Bowman a ’56 Corvette to sign, but Devine wouldn’t pull the trigger. Jones would later remind Devine of that fact multiple times by mailing him Press-Chronicle sports sections to St. Louis when Bowman appeared in stories with the Giants.

“He’d send Bing Devine a bunch of extra papers lying around the Press-Chronicle with articles on me with the Giants,” a chuckling Bowman said. “Finally, Bing told Carl Jones, ‘I get the point.’”

Devine, who began his career playing for the Johnson City Cardinals and was best known for getting Lou Brock from the Chicago Cubs in a “steal” of a trade, laughed it off some 40 years later while sharing memories of Jones.

Bowman grew up in the 200 block of Elm Street near the railroad tracks.

“I would stand on the railroad tracks with a stick and rocks,” Bowman said, “and pretend I was Ralph Kiner hitting home runs.”

Before he knew it, he was making a highlight-reel play at shortstop against the New York Yankees in the World Series, frog gigging with Don Larsen and swimming in Zsa Zsa Gabor’s pool.

Mays even introduced Bowman to basketball great Oscar Robertson, and “the Big O” came to Johnson City to speak when Bowman was inducted into the Northeast Tennessee Hall of Fame in 1993.

Bowman also became friends with the likes of Gaylord Perry and Lou Piniella along the way, and Tom Seaver thanked him in his biography for a productive mound visit.

“Seaver was struggling one day when I was playing second base (in the minors),” Bowman said. “I paid him a visit and asked him what his best pitch was. He said the ‘fastball.’ I said, ‘Well hurry up and throw it. The beer’s getting warm.’ …

“Sometimes it’s still a wonder to me – doing all I was able to do after coming off Elm Street at 140 pounds.”