By Trey Williams

Jeff Forney didn’t start as a 12-year-old on the Johnson City National team that won the 1976 Little League state tournament and got within a win of the World Series in Williamsport.

And he wasn’t offered a scholarship by successful East Tennessee State coach Charley Lodes, who did offer three of Forney’s Science Hill teammates – Jackie Cook, Billy Patton and Mark Hunter.

But Forney, who died unexpectedly last week at age 57, became a first-round draft pick of his beloved Cincinnati Reds after playing three years of college baseball (Roane State/Florida Atlantic). And after six years in the Cincinnati Reds organization, Forney began a successful career in coaching and individual instruction.

“Jeff was probably in the fifth or sixth grade and he’d tell me, ‘One of these days I’m gonna play baseball for Science Hill and I’m gonna play for the Reds,’” said Charlie Bailey, who coached Forney at Science Hill. “I can remember that like it was yesterday. … Jeff was special, that’s for sure. I was real proud of Jeff. He was a good athlete, but he was a heck of a worker.

“And he loved baseball. I mean I don’t think I’ve ever had a player that worked as hard and loved it as much as him.”

Forney played shortstop at Science Hill, which finished runner-up in the state to Germantown when he was a junior in ’81.

“Jeff had a really strong arm,” said Patton, who became an All-Southern Conference center fielder at ETSU. “I remember him always challenging (power pitcher) Mark Elrod to see who could throw the hardest. Now, Jeff didn’t always know where the ball was going, but he had a strong arm.”

Indeed, Forney had to switch positions with second baseman Tony Shade for part of his senior season because Forney began throwing wildly. Some attributed Forney’s wildness to pressuring himself while attempting to draw college attention.

“I’ve never seen Jeff upset, mad or even hardly down on himself,” said Jimmy Williams, Science Hill’s starting catcher in ’82. “He went through that little stretch his senior year where he had the yips or yikes or whatever throwing from shortstop, and they moved him to second base. And he never got down on himself or anybody. He’d say, ‘I gotta get better. Gotta get better.’

“He always had a smile on his face. He was a pretty happy dude.”

Forney was drafted after each of his two seasons at Roane State, but opted for Florida Atlantic, where he set school records with 46 stolen bases and seven triples in his lone season with the Owls. His speed, strong arm and a .575 on-base percentage helped him get drafted 19th overall by Cincinnati after that season.

“Coach Bailey always told me, ‘I remember you saying when you were a kid that you were going to play for the Big Red Machine,’” Forney said in 2007. “Lo and behold, I get drafted by the Reds and played my whole career with them.”

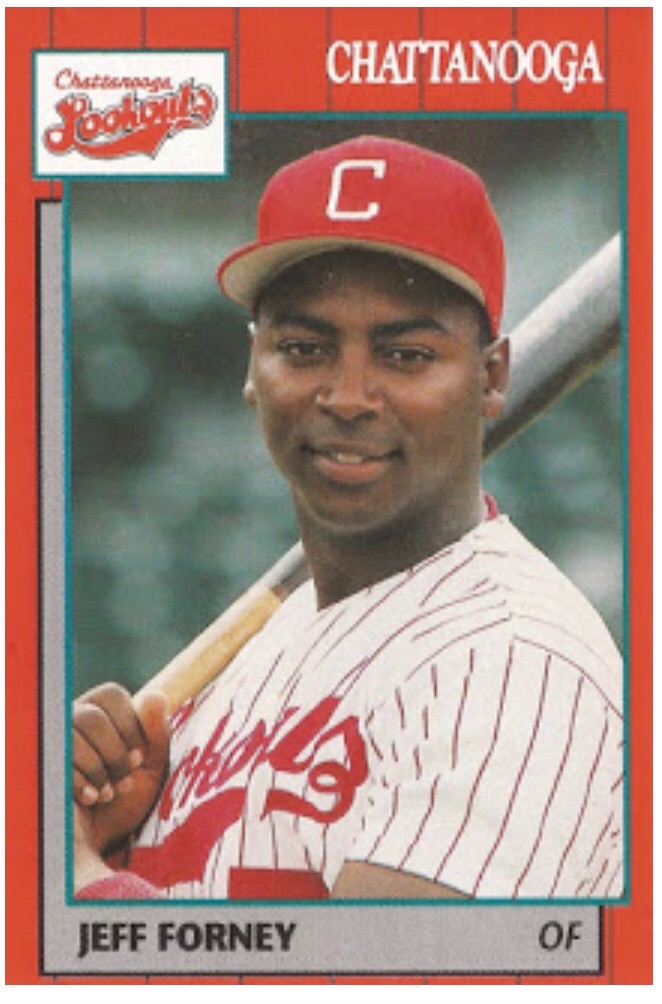

Forney was an All-Star for three different Cincinnati affiliates, including his final stop in Double-A with the Chattanooga Lookouts.

But a severe ankle injury cost him all but one game of the 1989 season in Chattanooga, and he was already 25 years old. Forney, who was converted to an outfielder after high school, bounced back to hit .278 in 1990 and led Chattanooga in walks, runs and triples. But his stolen bases fell from 30 to 10 in the first season after returning from the ankle injury.

“That ankle injury hurt (my dream of playing for Cincinnati),” Forney said. “And Eric Davis was a big detriment.”

Forney got into coaching following the 1990 season. He was an assistant at Notre Dame and Arizona State under former FAU player Pat Murphy, and eventually became the Arizona Diamondbacks strength coach.

A baseball junkie and a people person with a smile that’d light up a room, Forney became his own boss in 1999. The exercise science and physiology major authored baseball instruction books and designed training aids.

He and Murphy co-authored “Conditioning for Baseball.” Buck Showalter wrote the foreword.

Forney also created “Baseball Player University,” an instructional show he hosted that was picked up by Fox Sports Net.

Forney was interested in training and improving techniques at a young age.

“Jeff had a welding class at Science Hill,” Bailey said. “We didn’t have a weighted swing bat. We had the donut-type things.

“But Jeff took an old bat and cut the top out of it and filled it full of lead and then welded it back together, and that’s what we used as a warm-up bat. He was always thinking baseball.”

Williams, who moved from Cookeville to Johnson City in the ninth grade, said he was a 140-pound catcher for the Hilltoppers. He didn’t start until his senior season, and jokes that he probably only started at catcher in ’82 to keep from risking an injury to slugger Jackie Cook.

Williams said he hadn’t caught since Little League, but became the ’82 catcher thanks, in part, to supposedly being the only player on the bus with a cup when the ‘Toppers were going for a summer-league game at Sullivan Central.

At any rate, Williams hit four home runs as a senior (not bad when your home ballpark had big-league dimensions), which was second on the team to Cook’s 10. Williams attributed his surprising power to working out with Forney in the weight room below the old Science Hill gym.

“I was probably his first (training project),” Williams said while recalling lifting weights and the “Leaper” machine. “Jeff was so into that training back in high school. He wanted to stay longer than I wanted to stay, I can tell you that.”

Carl Williams, who coached Forney in fifth- and sixth-grade football and basketball at North Side Elementary, said Forney could’ve played three sports at Science Hill.

“He was like having a coach on the field – or the court,” Williams said with a smile while recalling the likeable Forney’s work at point guard, quarterback and safety. “He was a really good athlete and such a great young man.”

Along with coaching baseball, Bailey was an assistant basketball coach under Elvin Little at Science Hill.

“Jeff could’ve played basketball for Science Hill,” Bailey said. “He could’ve played football. There’s no question in my mind. But his number one goal was always to be a baseball player.”

Oddly enough, Forney briefly worried that his baseball career might be over after the Johnson City National Little League All-Stars’ 1976 season ended a win away from Williamsport, Pennsylvania. The summer league fields for teenagers weren’t as conveniently located as the Little League field, and Forney said transportation could’ve been iffy.

But his Kiwanis Little League team’s coach, Kermit “Popcorn” Laws, urged him to continue playing.

“Popcorn said, ‘If I have to pick you up every single day and take you to the baseball field, I’ll do that,'” Forney said. “And then, as I always say at camps, ‘The rest is history.’”

In a 2007 interview, Laws said Forney might’ve been his all-time favorite. He recalled the strong-armed Forney one-hitting the league champion Sockers.

“Even when he was a little boy, he was very dedicated,” said Laws, whose wife Jane instantly remembered how polite and friendly Forney and his younger brother, Fred Taylor, invariably were.

Science Hill finished state runner-up to Germantown in Memphis in 1981. Forney and Patton had Science Hill’s RBIs in a 6-2 state championship loss in Memphis. Forney was 3-for-5 and scored three runs when the ‘Toppers beat Baylor 19-10 in Chattanooga to reach the state championship series.

Many of the players on the ‘81 team, including Forney, Cook, Hunter, Patton, Mark Elrod and Jimmy Street, were juniors who’d been on the Johnson City National Little League team that finished runner-up in the Southeast Region in St. Petersburg, Florida.

There was no ESPN at the time. One more win, however, and the Nationals knew they could’ve been on ABC’s Wide World of Sports. But they lost in the regional championship game to a team from Tuckahoe, Virginia.

“I never will forget that chant: ‘Go, Go, Tuckahoe,’” Forney said. “Just saying it still can (strike a nerve). I remember, man, we were crying and crying.”

The hard-throwing Elrod was a workhorse on the mound for the ’76 and ’81 teams.

“If we’d had one more day of rain in Memphis,” Bailey said, “I’d say we would’ve won the state (in ’81). Mark Elrod could throw a baseball.”

Elrod was a senior in ’81, but Science Hill appeared capable of outscoring any opponents in ’82 thanks to the return of seven starters.

And the high-scoring Hilltoppers set a program record with 27 victories and piled up runs like cordwood most of the season. But their season screeched to a halt with a 1-0 regional loss to David Crockett, which entered with a 15-13 record.

Forney’s cousin, Tary Scott, tagged up and scored the winning run after a controversial call at the plate that Scott later said was incorrect.

“Mark Hunter threw it and I tagged him out,” Williams said. “Tary even said he was out in the paper. … But still, we hadn’t scored either. Their pitcher (Billy Cartwright) pitched a great game.”

The disappointment was still in Forney’s voice 26 years later.

“Man, I still remember that to this day,” Forney said. “I believe we’d dusted them twice during the season and everybody was kind of taking them for granted. And you know how baseball is: before you know it, we were walking off the field.”

The state runner-up finish in ’81 wasn’t nearly as disappointing as the way Forney’s senior season concluded.

“We came up one game short in ‘81,” Forney said, “but that whole junior year was really special. We were a tight-knit group. We hung out a lot outside of baseball. I remember some good things that probably wouldn’t be good to put (in the newspaper).

“Coach Bailey emphasized ‘team.’ There were no hot dogs or no one person; it was everybody. And we had guys who came from all walks of life: Keystone, the projects, all different neighborhoods and backgrounds.”

Many of the players played in the same leagues from ages 9-18. Lifetime bonds were built.

Edwards, the uncle of former Pittsburgh Pirates first baseman Will Craig, was one of those players. So when he was on his honeymoon in 1987 at Disney World and noticed in the sports page that Forney’s Tampa Tarpons were playing nearby, well, it became a honeymoon with two diamonds.

“I got to looking and I said, ‘Jeff’s playing down there at Vero Beach tonight. You wanna go,’” Edwards said. “Here you are on your honeymoon and we go to a baseball game. Of course, she’s kind of a tomboy and likes baseball and stuff.

“So we went and got to talk to him. Matter of fact, we got a foul ball, which was pretty neat. He was surprised to see us.”

Edwards was proud and happy to see Forney’s hard work paying off.

“We were friends since Little League, and Jeff really wasn’t the best Little League player,” Edwards said. “But he kept getting better and better and better and better. I don’t know that he was the most talented person on that Science Hill team – probably Billy Patton or Jackie Cook. Jackie was probably the best hitter and Billy Patton was probably the most talented. But Jeff was the hardest worker.”

Edwards didn’t play college baseball. He said when Forney would come home while playing in college, he’d have Edwards go to load baseballs into the pitching machine that Bailey had put in the auxiliary gym in Freedom Hall.

“When Frog (Forney’s nickname since childhood) would come in for the holidays or whatever, he would say, ‘Let’s go hit,” Edwards said. “So basically that meant that I would go up there and feed him balls with that ole blue pitching machine.”

Patton, who became an All-Southern Conference center fielder at East Tennessee State, seems to wonder what he might have become with Forney’s work rate.

“To me, Jeff was most definitely the hardest-working player I probably ever played with,” Patton said. “I mean he just loved the game. He loved playing.

“I think if we were all like that, we probably would’ve been a lot better. To be totally honest, we actually didn’t work as hard at the game as he did. I can admit that 30 years later.”

Jimmy Williams was also impressed by how hard Forney worked at instruction and hosting a TV show.

“He had a great career,” Williams said. “I mean you’re the strength and conditioning coach for the Arizona Diamondbacks. Come on, man. That was pretty cool.

“He was a humble dude. I never saw him mad.”

Williams had been in contact with Forney through the years, but hadn’t seen him since attending the funeral for Forney’s mother Ruby not too many years after their high school careers concluded. Williams’ voice cracks with emotion while recalling the positivity somehow mustered by a grieving Forney.

“I was upset and he came over to me and said, ‘What’s wrong Jim,’” Williams said. “And I was like, ‘Man’ and he said, ‘Nah. She’s happy.’ He was consoling me at his mother’s funeral, and that’s what I remember.

“His mom was a wonderful person, my Lord. I didn’t know her well, but she was just one of those people – they were humble and happy people.”

Since Forney’s death, Williams has watched a video of Forney talking about his Christian faith for his church some two weeks before his shocking death. Forney talked about being spiritually prepared for death. The timing was encouraging, if not eerie.

It reminded Williams of Forney’s mother’s funeral and how confident Forney had been in the belief that his mother was in a better place.

“Death is terrible on a family – terrible,” Williams said (Forney has a wife and five children). “But Jeff knew where he was going, knew what his vision was. Now, he probably didn’t think he’d be gone in a month.

“Gosh, I just remember the last time I saw him at his mom’s funeral, and he comforted me more than I comforted him. Jeff Forney had a vision. Jeff was a good guy to be around.”

Bailey and Carl Williams would attest to that. They worked for the Johnson City Parks and Rec in the ‘70s, and one of their duties was managing Science Hill’s old gym downtown.

Forney, then 11 or 12 years old, would often hang around and help, they said, without even the promise of the change or few dollars he usually pocketed.

Back then, you might see Forney, looking snazzy with an afro and blue canvas sneakers, singing and dancing when “Car Wash” came on custodian Willie Mustain’s radio.

Forney laughed when Mustain’s name was mentioned more than 30 years later.

“You knew if it started getting cold in that gym,” Forney said, “that Willie’d had one nip too many and let the fire in the furnace go out.”

Bailey said Forney was thoughtful and beyond his years as a child.

“My wife and I just had one car at the time,” Bailey said. “She’d get there to pick me up some nights before we were through. Well, Jeff would say, ‘Coach, I’m going to go on out there and make sure nobody bothers her.’ Jeff was special.

“All coaches like winning games and, of course, it helps pay the bills. But the real reward is seeing kids turn out like Jeff Forney did.

“Jeff was just an outstanding person. He was an accomplished coach. He was an author of books on baseball. And from what I can understand, he was really involved in his church in the community out there. He was well thought of, and that’s how I’ll remember Jeff.”